For years, cycling training has revolved around a single question: Is my fitness going up or down? Historically, we’ve tried to answer that with one primary metric – usually FTP – and one broad measure of training load. A new study based out of the University of Calgary is recruiting participants remotely to study how to quantify training load more realistically across multiple physiological systems. Read on to see what the study is about and contact Scott Steele if you’re interested. All that’s needed is you and a smart trainer!

Anyone who races, sprints, climbs, or survives repeated attacks on group rides knows that fitness isn’t one-dimensional. I wrote about this in more depth back in November (Why FTP isn’t enough). It seems obvious that short, explosive power responds to training differently than sustained aerobic intervals and that fatigue doesn’t affect all systems equally. And yet, most training models still try to compress all of that complexity into a single score of fitness & fatigue.

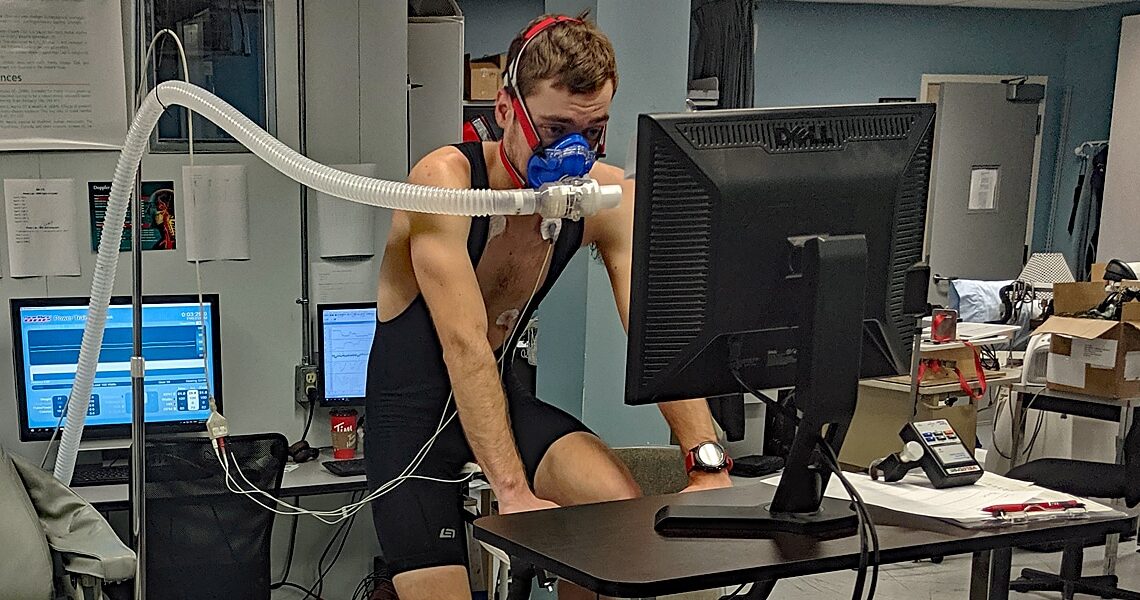

This gap in knowledge between applying training strain to different energy systems and actual changes in performance is exactly what an ongoing research study called 3Dapt is trying to explore. And over the next 16 weeks, I get to be one of the participants! It’s my first time serving as a research “guinea pig” since completing my Master’s work at Brock University.

Figure 1. One of the last times I was a guinea pig for science, completing pilot work for my Master’s with Dr. Stephen Cheung’s Environmental Ergonomics Lab at Brock University.

Interested in Learning More or Participating?

The 3Dapt study is currently nearing the end of its recruitment phase, but there may still be opportunities to learn more or express your interest in participating. If you’re curious about the study, what’s exactly involved, or whether you can participate, feel free to reach out to me directly. I’m happy to share additional details and can help connect interested riders with the study’s primary investigator, Dr. Hilkka Kontro at the University of Calgary.

What Is the 3Dapt Study?

The 3Dapt study is an 18-week remote cycling study designed to examine how different physiological systems adapt in response to different types of exercise strain.

Rather than assuming fitness changes uniformly for athletes, the study treats fitness as multi-dimensional, tracking how short-duration, medium-duration, and long-duration performance evolve independently over time. Participants continue to train in the real world – structured or unstructured – while providing frequent performance data that allows researchers to link what kind of training stress was applied to which performance changes followed.

In short, it’s an attempt to better map the individual training-to-performance relationship, rather than relying on population averages. Many traditional training studies take the opposite approach: prescribing the same training program to a group of cyclists and reporting the average change in fitness that follows, suggesting that the training intervention impacts all athletes similarly.

What the Study Measures

Throughout the study, three broad categories of data are collected:

- Training load, broken into three distinct strain categories (Peak, High, & Low)

- Cycling performance, measured through maximal efforts at short, medium, & long durations

- Physiological and subjective responses, including heart rate and perceived exertion

Rather than prescribing a rigid training plan, the study intentionally allows athletes to train as they normally would, with one important requirement: introduce a meaningful change compared to the previous couple of months.

For me, this will mean deliberately emphasizing more top-end sprint work and high-intensity intervals, alongside a clear increase in low-intensity volume as spring and the outdoor season approach. The goal is to create a clean signal between training emphasis and performance response. Simply put, if my goal is to create measurable changes in my sprint & high intensity fitness, then I’ll need to apply a strong training stimulus on those systems!

Weekly Testing

To track changes over time, participants will complete one rotating performance test each week:

- Short test (5 seconds): Reflects maximal power (Peak Power/Pmax) the most

- Medium test (1–3 minutes): Reflects high-intensity, glycolytic capacity (W’/HIE) the most

- Long test (10–12 minutes): Reflects aerobic, sustainable power (CP/Threshold Power) the most

Each test targets a different performance system, allowing the researchers to observe how each one responds – independently – to various types of training stress & fatigue. While these parameters can be calculated automatically through breakthrough efforts in Xert, standardized tests are required here to fit a consistent three-parameter power-duration model across the full study period.

For the medium and long tests, participants are allowed to select their preferred duration and stick with it for the duration of the study. I opted for a 3-minute medium test and a 12-minute long test, favoring slightly longer efforts as a better representation of my sustainable performance. I’ve always struggled with 1 min all-out efforts in both running and cycling.

My Baseline Testing Results

Before my training phase began, I completed all three baseline tests while still recovering from a minor cold. I was thrilled to achieve over 1000 W for 5s in the short test – on a turbo trainer nonetheless! As a relatively lighter rider (68.6 kg), I’ve never been a particularly strong sprinter.

Figure 2: Short Test: 5 second power = 1007 W (14.68 W/kg).

For the medium and long tests, I was generally happy with how my efforts were paced, though I felt I underperformed slightly.

Xert appeared to support that perception: my MPA was pulled down substantially in both tests, but didn’t quite converge with my actual power output at the end of either test. With a perfectly executed, truly maximal effort, I’d expect my MPA to meet my power right at the conclusion of the test. Even so, while the results may not be perfectly ideal, they provide a solid and informative starting point.

Figure 3: Medium Test: 3 min power = 359 W (5.23 W/kg).

Figure 4: Long Test: 12 min power = 289 W (4.20 W/kg).

These tests provided a starting point for me across all three dimensions. They also highlighted something I already suspected: while my aerobic base is quite good, there is significant room for improvement in my short-duration, high-power efforts. Since I’ve gotten heavily involved with Zwift racing this winter, those short, hard efforts are exactly where I plan to focus my training over the next 16 weeks.

That’s all for this month. Stay safe, warm, and ride fast! I’ll see you next time!

Interested in Learning More or Participating?

The 3Dapt study is currently nearing the end of its recruitment phase, but there may still be opportunities to learn more or express your interest in participating. If you’re curious about the study, what’s exactly involved, or whether you can participate, feel free to reach out to me directly. I’m happy to share additional details and can help connect interested riders with the study’s primary investigator, Dr. Hilkka Kontro at the University of Calgary.

The post The 3Dapt Study appeared first on PezCycling News.