Cycling is a sport that is ideal for photographic interpretation: the breath-taking landscapes, colourful kits, elegant bicycles, and close-up human interest, whether of racers battling it out, mechanics at the ready, or Belgians drinking beer by the roadside. For many in the past it was hard to conceive of photography as a fine art rather than merely some kind of mechanical/chemical reproduction but the 20th Century saw its acceptance due in large part to photographers working for the Magnum Photo collective, established in Paris in 1947. “Magnum Cycling” is an impressive book that has come from the archives at Magnum, a sampling of unexpected treasures that will leave you wishing for more.

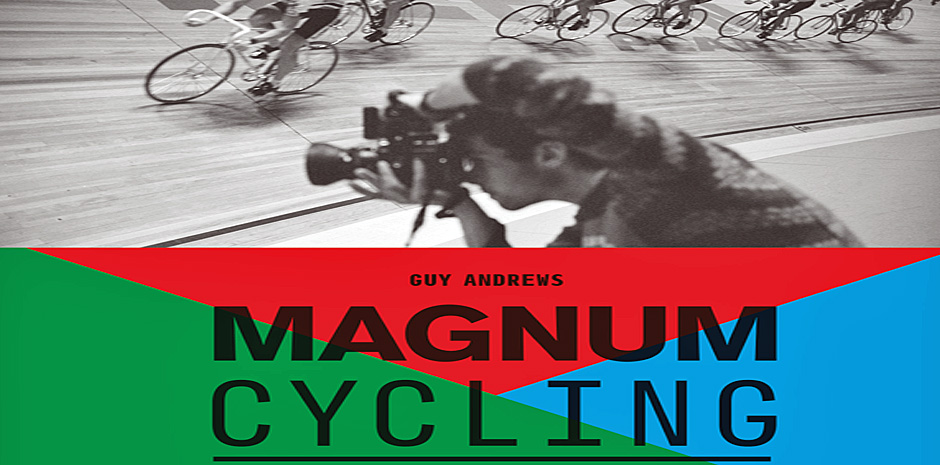

Magnum Photo was a new idea when launched by a group of photographers that included Robert Capa and Henri Cartier-Bresson, now legendary figures in the art: a collective of those who actually made the art. What is novel about this book, edited by Guy Andrews (formerly Chief Editor of Rouleur magazine for a decade), is that the photographers featured were not specifically sports photographers or journalists. Rather, they came to the races with a different way of seeing and the result is a rich and striking collection of images, primarily in black-and-white but also some that remind us of how beautiful Kodachrome images were before that film vanished in 2009.

The six chapters of the book are arranged thematically, and accompanied by a thoughtful and insightful text by Mr. Andrews, who serves as the interpreter here between fine art photography and cycling history.

This image is the first of a pair of images that was intended as a diptych, the switching of heads from right to left perfectly suggesting the movement of the passing peloton. Capa has succeeded in capturing what the race is like from the spectator’s point of view.

The book begins impressively, with Robert Capa’s images from the 1939 Tour de France, where his technical innovation was to use a 35 mm camera, something much more versatile than the bulky gear favoured by newspaper photographers of the day. Capa also shot some images from the back of a motorcycle, commonplace today but taking some courage in those days of potholed roads and rather primitive motorbikes. As Guy Andrews notes:

- “The action taking place around the race seemed to have occupied Capa much more than the race itself—a unique approach in the late 1930s, and one that has ensured that his pictures remain fresh and alive….Many of the photos seen here were not used at the time, which in retrospect is rather a shame; much of what Capa shot of the 1939 Tour was some of the finest photography the race has ever seen.”

By 1939, Tour organizers had realized that split stages were better not only for the racing but also for the rider’s welfare. The French riders in particular were probably delighted when lunch became a regular occurrence—albeit between stages. Cleaning up at a garage was also a daily routine.

In 1939 riders still had to use bicycles supplied by the Tour’s sponsor, L’Auto. They were not popular with the competitors, looking like a collection of holiday-hire bikes compared to the refined, custom-made machines the riders would normally have ridden.

French photographer Guy le Querrec, a passionate fan of bike racing, is featured next. Although he is noted for his portraits of jazz celebrities, his enthusiasm for cycling shines through in his interview with Andrews when he talks about his “third good photograph,” taken as a roadside spectator at the 1954 Tour de France when he as thirteen years old. He was invited to photograph the 1985 Spring training camp of the Renault-Elf team, and these images, as well as of star Laurent Fignon in Provence, and the French Cyclo-Cross Championships that same year, are an excellent documentation of the life of pro cyclists nearly 35 years ago. More cyclo-cross follows, with the work of Belgian John Vink, and show the grass-roots (and very muddy!) nature of this sport in its heartland.

Team members Philippe Chevallier, Pascal Jules, Bruno Wojtinek and Chirstian Corre take a drinks break during training. Hot tea and soup are often drunk when it’s this cold.

Vossem, 9 October 1982: When riding through mud, technique is everything. The bike tends to slide away in every direction, making progress extremely difficult. The best cyclo-cross riders are those that manage to stay relaxed and focused on the bike. If you tense up, a crash is inevitable.

The work of another Belgian, Harry Gruyaert, brings us into the world of colour at the 1982 Tour de France. Not attached as an official photographer, he was actually doing projects for the Elf oil company, one of the sponsors of the Renault-Elf team of Bernard Hinault, and was sent by Magnum to cover the final week of the Tour. Andrews writes: “In 1982 most of the Tour de France photographers were taking pictures for newspapers, which at that time meant working in black and white. As a result, there isn’t a lot of colour work of that year’s race.” Gruyaert’s images are bright and sunny, and even in the 1980s it feels like a very different era. Just check his photo of the riders taking a break in the middle of the road due to a blockage by striking farmers! On the other hand, the spectators by the side of the road are still there now…

The riders are forced to take a break by protesting farmers. On the right of the photograph, in the French tricolor jersey of the national champion, is the late Régis Clère. He is also wearing the yellow cap of the leading team on general classification, which at that point was Coop-Mercier. The light-green caps, sported here by members of the Raleigh team, are worn by the team with the most points.

In 1982 the Tour de France consisted of 170 riders—seventeen teams with ten riders each. By 1987 teams could only have nine riders each, numbered 1 to 9, 11 to 19, 21 to 29, and so on. In 2015 there were twenty-two trade teams with nine riders per team. The leader of each team always wears the first of the team’s nine numbers (i.e. 11, 21, 31 etc.), with number 1 itself being reserved for the defending champion, and 2 to 9 for the members of his team.

The book moves indoors next, with a selection of fine photographs of track racing. Besides the action in Paris and Ghent at the Six-Day Races by various photographers, there is a selection of good colour images from the 1996 Paralympics in Atlanta taken by Chris Steele-Perkins, who took an apartment near the Olympic park and just strolled in each day, a much easier shooting opportunity than the Olympics proper but which yielded some striking pictures of an event that was a lot more low-tech than today.

Racing at the Bercy Arena didn’t last long, and the Paris six-day was abandoned in 1989. The love of six-day racing has diminished in recent years, with the focus being more on the drinking and late-night dining than the racing.

Antwerp, 12 February 1984: Pacing riders also wear special helmets with rear-facing ear holes in the sides, so that they can hear the cyclist’s instructions. Although noisy, the motorbikes add excitement and speed to the whole spectacle.

The Swiss cyclist Beat Schwarzenbach competes at the Stone Mountain Velodrome in Stone Mountain, Georgia, during the 1996 Atlanta Paralympics.

“Although [Henri] Cartier-Bresson’s name might not be the first that comes to mind when thinking of sports photographers, the velodrome is in many respects the ideal subject for reportage and documentary photography, with the crowds providing just as much interest as the racing whirling around you. And unlike the Tour de France, you are permanently at the centre of the action.” Cartier-Bresson found himself at the 1957 Paris Six-Day Race and the photos in the book confirm his unmatched reputation as someone who could focus on human interest in images that are compelling in their spontaneity. And sometimes hilarity, as the photo of the racer reading the newspaper while sitting on his track bike.

The most exciting point of any six-day race would be the final evening. In order to keep the stands full and the media interested, the racing would usually be kept quite tight up until the last few laps. The MCs for the evening would help build the anticipation.

During their downtime, the riders developed some fairly impressive skills. Allegedly, they could even sleep on their bike while riding, if supported by a teammate on either side. Such skills as riding backwards and standing still for minutes at a time were regularly shown off at the track center.

The book concludes with a chapter of John Vink photos from the 1985 Tour de France that he took for the French newspaper Libération although he had proposed a completely different project of submitting a photo of Italy every day. Not a sports journalist, he remarked to Andrews: “I was not interested so much in having a picture of the winner or loser—it was not an assignment to do specific things. [It was a] dream assignment, to do whatever I wanted. They had to have the atmosphere; if there was one of a winner too, then all the better.”

Stage 8, Sarrebourg to Strasbourg time trial, 6 July 1985: If the top of the results board were visible, it would show that Bernard Hinault had dominated the day, beating his nearest rival, Stephen Roche by a massive 2 minutes and 20 seconds.

The unavoidable Lance Armstrong also appears as a photo subject as Christopher Anderson was assigned to take some up-close and personal photos for Esquire in 2004, an assignment that ended up disappointing fan Anderson. But on the subject of fans, the final chapter presents a wonderful series of photos from the roadside and inside bars and elsewhere of the spectators who add so much colour to the world of professional cycling with their enthusiasm.

Guy Andrews’ introduction notes: “There is still nothing to prevent anyone from bowling up to the start of a bicycle race and taking photographs. But, as this book shows, Magnum’s finest photographers provide a uniquely timeless view of cycle racing. Photography is so often about capturing the moment, and cycling is all about moments: the anticipation, the team cars, the police, the journalists, and the whole multicoloured circus before the race has even arrived. And when it does, it’s through and gone in a heartbeat.” “Magnum Cycling” captures many of those moments beautifully; it could have been triple the length and still not be enough.

“Magnum Cycling”

Edited by Guy Andrews

254 pp., hardcover, more than 200 illustrations in black and white and colour

Thames & Hudson, London, 2016

ISBN 978-0-500-54457-0

Suggested Price: US$50/£32

• BUY IT On AMAZON HERE

The seasoned Tour rider knows that the real racing starts some 20 km (12½ miles) from the end of each stage. On the flat sections, as here, this results in a speed increase to a “line out” the race. In the mountains, it usually means a long climb to the finish. After three weeks and 3,500 km (2,175 miles), a rider finishing the Tour will have shed several kilograms in weight and put in around 500,000 pedal strokes.

The post PEZ Bookshelf: Magnum Cycling appeared first on PezCycling News.