After Tadej Pogačar’s run of success at the Giro and Tour de France last year, let’s turn back the clock and look at the life and world of the first racer to win the Giro and the Tour in a single year: Fausto Coppi, Il Campionissimo.

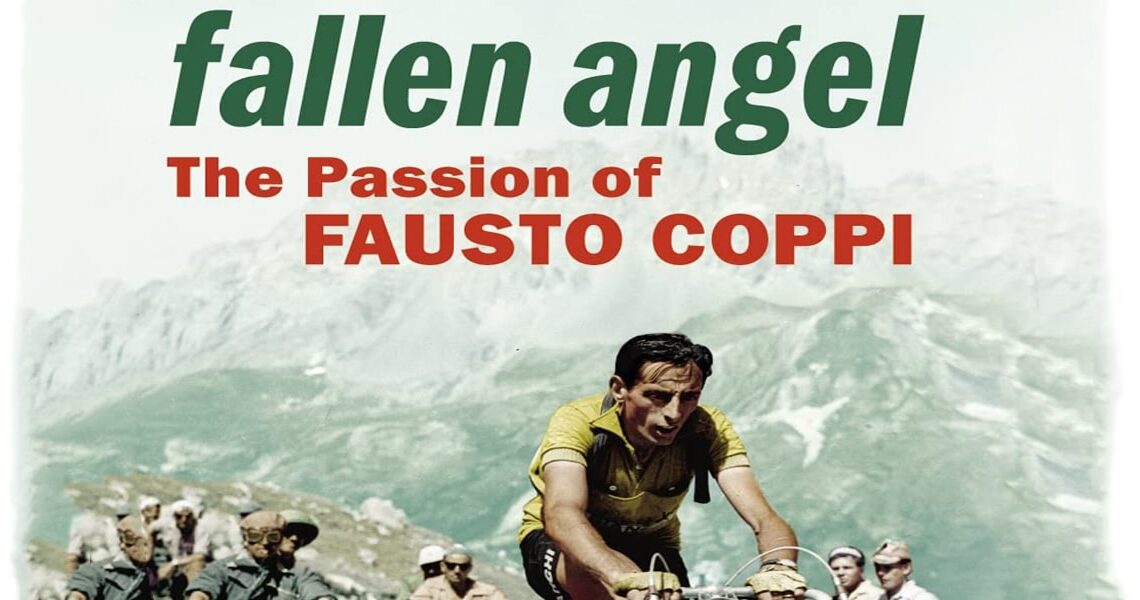

When Fausto Coppi accomplished his remarkable double in 1949, he had already become the idol of Italy. He first won the Giro in 1940, unheralded and at a mere 20 years of age, and had gone on to hold the World Hour Record, set during the war in 1942 and unbroken until 1956. In the 1946 Milan-San Remo he attacked five kilometers into the nearly 300 km-long race with a small group and dropped his breakaway comrades on the Turchino Pass, sailing alone into San Remo with 14 minutes in hand. And this was just the beginning, as British journalist William Fotheringham recounts in his absorbing book, the first English-language biography of Il Campionissimo, “Fallen Angel: The Passion of Fausto Coppi.”

Fausto Coppi, also nicknamed “the Heron” because of his exceptionally long legs, had an unimpressive beginning as the son of a peasant household in Piedmont, in a village that has continued to decline since his birth in 1919. A serious child, he found enjoyment in riding a too-large cast-off bicycle, although when he played truant from school at age 8 his aunt, who was his teacher, made him write a hundred times: “I must go to school and not ride my bicycle.” At 12 his schooling ended as he left home, typical of the time and place, and his bicycle was key to his employment as a delivery boy for a butcher.

And here the legend begins as gangly young Coppi is “discovered” by Biagio Cavanna, a once-promising bike racer turned boxer (surely a unique career path) who, as he became a victim of blindness, turned towards the management of pro cyclists. Soigneurs of the day carried a powerful mystique and none more so than Cavanna, a heavy-set man with omnipresent sunglasses, “[who] inspired both fear and faith among those he treated.” He was the first of the strong personalities who would surround Il Campionissimo.

Under Cavanna’s disciplined tutelage, the peasant boy went from a strong but hopelessly awkward rider to become one of the peloton’s most stylish cyclists ever. In eighteen months his rise was meteoric, from winning races for 50 lire and a salami to being tipped as the Next Big Thing in Italian racing. In April 1939 he first raced against Gino Bartali, the first whisper of what was to become a long-standing, complex (and profitable) relationship, and in 1940 had his first professional contract with Bartali’s Legnano team. In the Giro d’Italia that year, Bartali hit a dog and crashed, dislocating his elbow. Although he stayed in the race, his injury prevent him from staying with the leaders and, to universal amazement, it was the unknown Fausto Coppi who wore the maglia rosa on the last day in Milan.

War came and Coppi was in the military but able to continue cycling for a time. With no races to build his reputation, it was decided that he would try for the World Hour Record. At the Vigorelli velodrome in 1942 he squeezed out a margin that would make the title his at 45.798 km, a record that stood until 1956. But events caught up and his cycling career was derailed as he served in North Africa and ultimately became a prisoner of war of the British and even contracted malaria.

The war ended, it was as if the interruption had meant nothing to him in sporting terms as in 1946 he compiled an impressive list of victories, including Milan-San Remo, the Giro di Lombardia, the Grand Prix des Nations and three stages of the Giro d’Italia. The legend grew as Fausto Coppi, with his powerful Bianchi team, made his way through the rubble of the smashed nation that was post-war Italy. With his elegant style and distinctive appearance, he was a winner to his disheartened countrymen. His popularity grew throughout Europe and a French journalist is even quoted as saying that Coppi’s popularity in France helped overcome the ill-will and distrust between France and Italy after the war.

The author interviewed people with first-hand acquaintance with Fausto Coppi but as the victories mount up the peasant boy from Castellania disappears from the book to be replaced by a powerful yet undefinable presence. Coppi was a reticent man and even his intimates have trouble recalling his personality, particularly compared to other characters of the time such as the chain-smoking, larger-than-life Bartoli, or even his own brother Serse, a life-of-the-party type who was a teammate (and Paris-Roubaix winner) and who was to die tragically after a crash at the Giro di Piemonte in 1951. Fausto Coppi was superstitious and fragile, and suffered from bouts of self-doubt so strong that he wanted to quit races or leave the sport altogether. He was injured in serious crashes. Shattered as he was by his brother’s death, his defence of the Tour de France in 1951 was unsuccessful and he won little that year. But he then went on to win the Tour de France in 1952 by more than 28 minutes after winning the Giro d’Italia for his second Grand Tour double. In 1953 he became World Champion, and then the inevitable decline began. He was still racing in 1959, a pitiable shadow of what he once was, ravaged by dope and pushed uphill by his teammates.

It is clear that Fausto Coppi approached cycling in a new way, developing with Cavanna revolutionary training methods. The Bianchi team was used in a modern, tactical way to support its captain and Coppi took pains over equipment, bringing with him a mechanic from Legnano who was to stay with him for his whole career. Much was made over personal presentation and cycling took on air of professionalism it had never had before. The ideas of Fausto Coppi were passed on to the teams of successful champions–Bobet, Anquetil, Merckx, Hinault, Indurain, Armstrong–in the years following. And Coppi, of peasant stock, was immaculately groomed, wore beautiful suits and drove luxurious cars, the athlete-as-movie-star.

But all this success is overshadowed by the last part of the book. Fausto Coppi had grown apart from his wife and entered into a relationship with Giulia Occhina, an army doctor’s spouse, in 1953. This caused an enormous scandal in Italy and the author describes the circus surrounding the affair. It is incredible to us now but 55 years ago Italian police could break into a house to determine if a couple were sharing the same bed. Those who had cheered Coppi on the road now spat on him but as his career ended he still went his own way and kept his own counsel, perhaps befitting a man who succeeded best at lone breakaways. The interviews with those who were there nearly six decades ago reveal the deep feelings, and more than a few scars, that still exist to this day. And yet, for all the scandal, Fausto Coppi remains loved in Italy.

His palmares are astonishing, especially given the interruption of the war years: the Tour de France (twice); the Giro d’Italia (five times); Giro di Lombardia (five times); Milan-San Remo (three times); Grand Prix des Nations (twice); Paris-Roubaix; La Flиche Wallone; World Champion (on the road in 1953, and twice on the track in Pursuit); the World Hour Record. He was a superb climber as well as a superb time triallist. A French journalist, Pierre Chany, wrote that between 1946 and 1954, once Coppi had broken away from the peloton, the peloton never saw him again.

The final unexpected dramatic turn was Fausto Coppi’s death at the age of 40 in January 1960 following a hunting trip in Africa where he had contracted malaria and which Italian doctors failed to identify in time. Even this is surrounded by controversy.

“Fallen Angel: The Passion of Fausto Coppi” unfolds like a novel, and it is clear why the myth of the tragic champion continues to hold the popoular imagination. The highest point in each year’s Giro d’Italia is the Cima Coppi. There are monuments to Il Campionissimo on the roads he raced on; his house became a museum in 2000; a brand of bicycle still bears his name. Even places unconnected with him seek connections: there are restaurants in Toronto and Washington, DC, named after him, and even my old racing team in Washington is named Squadra Coppi.

William Fortheringham’s extensive research and sympathetic writing helps us to understand the grip Fausto Coppi’s story still has on us. Everything in this book seems larger than life, and it must be highly recommended for those wanting to know more about the Golden Age of Racing and the steep climbs and terrifying descents of sports celebrity.

Fallen Angel: The Passion of Fausto Coppi by William Fotheringham

304pp., illustrated, available in hardback, softbound and Kindle editons

Yellow Jersey Press, London, 2009

ISBN 978-022-407-4476

# Fallen Angel: The Passion of Fausto Coppi is available from AMAZON.COM. #

The post Bookshelf: Fallen Angel appeared first on PezCycling News.